Writing is a big part of my job. I write lectures, papers, book chapters (…book!), presentations, grant applications, blog entries, feedback, emails, reports, reference letters, and probably a bunch of other things. Yupp, a lot of my job involves writing. But just because I write a lot, doesn’t mean I’m any good at it. I can’t be that bad, I do have citations of my work, but there is always scope to improve. So how to go about improving?

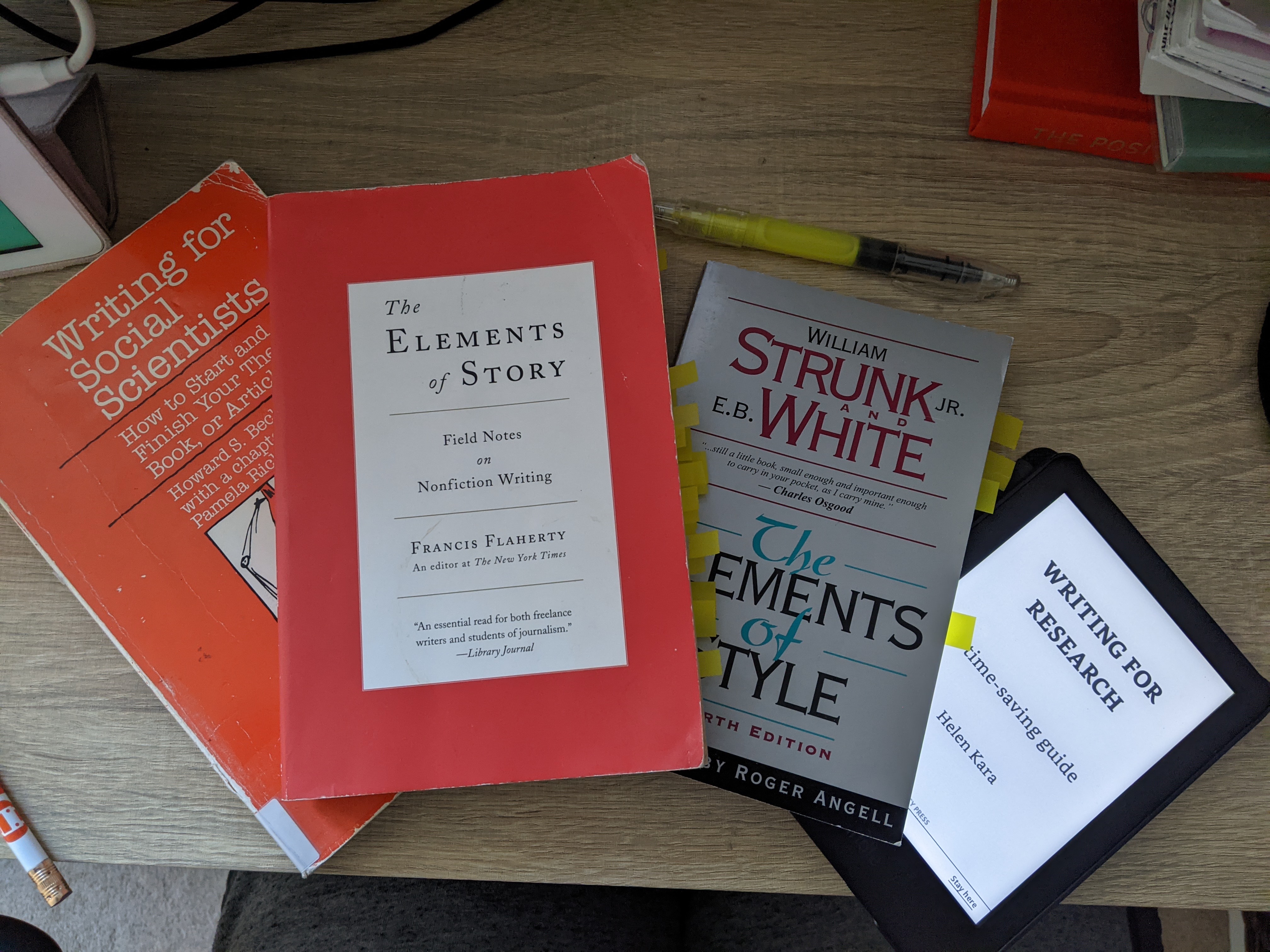

Like any good nerd, I decided that reading up on the topic is the best solution. I actually started thinking about a need to improve my writing after a friend recommended me the book Elements of Story in March 2021. Since then, I expanded my reading list with Strunk and White’s classic reference book Elements of Style, Howard Becker’s Writing for Social Scientists, and Helen Kara’s Writing for Research.

A key ingredient for better writing suggested by all these books is editing. Everything comes down to editing and revising your writing over and over and over again. I also found some specific issues which help with key questions such as: where to start?, how to be clear? and how to be engaging? I detail these key takeaways below.

DISCLAIMER: This is by no means a summary of the content of these books, it’s just some notes for my future self (and anyone interested) on what I thought I would focus on. For anyone with the interest and time, I would recommend reading these books for themselves, as they all offer unique and helpful insights into different but related elements of the writing process.

So in no particular order, here are some key things I’ve learned.

Just write

Writing for Social Scientists and Writing for Research are both clear on this.

“If you want to be a good writer, the first thing you have to do is write.”

This can be daunting, and many people will priorities other tasks (cleaning the house, baking cookies) because they find it hard to get started.

One reason might be that academics expect their writing to be flawless at the moment they put pen to paper (fingertip to keyboard?). This is a myth. The sooner you allow yourself to just write, without the pressure for it to be perfect, the sooner you can start to actually write. In Writing for Social Scientists Becker says to just “write anything”:

“Once you know that writing a sentence down wont hurt you, know it because you have tried it, you can do what I usually ask people to try: write whatever comes into your head, as fast as you can type, without reference to outlines, notes, data, books, or any other aids. The aim is to find out what you would like to say.”

In Writing for Research, Helen Kara recommends trying out the technique of “Freewriting”. In freewriting you set a prompt related to your project, and then write for ten minutes about it, writing anything that comes to your mind. It doesn’t have to be good, it just has to be written.

Once you have started writing, it is much easier to continue on.

Where do I start?

Great, you are ready, you can start writing. But where to start?

My students tend to think writing is a linear process, so I find myself explaining this in dissertation meetings every year: there is no need to write in the order in which the paper will be read.

For data analysis coursework, I usually advise students to start with their research question, their methods, and then their results. This fits with Kara’s observation in Writing for Research that:

“[writing] often starts in the middle.”

But there is really no wrong place to start writing a paper. In Writing for Social Scientists, Becker suggests to:

“Do whatever is easiest first.”

Another approach is to tailor your writing to the environment in which you will be working. In Writing for Research, Kara gives the example of working on a train: with no access to internet or reference material, she will write a section which doesn’t need these resources. She also suggests leaving notes such as “reference this later” or “link this section to the next” as a solution not to get stuck, but be able to continue the flow of writing.

The first draft of everything is shit

I had originally seen this quote attributed to Hemingway but I saw this quoted again in Writing for Research as “The first draft is always shit.” said by Elmore Leonard^[Side note: there is an actual book called ‘Hemmingway did not say that’ for quotes misattributed to Hemingway apparently…].

This snappy line drives home the point that editing is a crucial part of the writing process. Writing is not just the creation of the content, but the rearranging and deleting of that content as well. In Elements of Style Strunk and White say:

“Revising is part of writing..”

In Writing for Social Scientists, Becker explains that in undergraduate education, students work to tight deadlines^[often self imposed: if you are a procrastinator, I recommend a full read of Helen Kara’s Writing for Research for helpful tips]. This means that the first draft is often what is handed in, and this puts us into a bad habit of expecting a first draft to be good. Splitting with this notion will greatly help your writing.

“Knowing that you will write many more drafts, you know that you need not worry about this one’s crudeness and lack of coherence. This one is for discovery, not for presentation.”

Understanding this is a big step in moving from the writing process typically used for undergraduate essays to producing better writing, at all stages.

The schedule for editing can vary. Ideally, you want to leave as much time between writing and editing as you possibly can. Becker describes his process in Writing for Social Scientists where he writes over summer, then edits throughout the semester, when demands on his time are greater (i.e. teaching). Helen Kara gives this general guideline:

“You need to leave your draft alone for a while so you can come back to it with fresh eyes. A month is good; six weeks is better.”

How many iterations your paper will go through will vary. Based on my reading of Writing for Social Scientists it sounds like an upper bound on the number of revisions may not exist. More tangibly, Writing for Research suggests three drafts (although this is qualified as at least three drafts):

“The first draft where you churn out the words, the second where you knock it into shape, and the third where you review your word choices, grammar, and structure.”

And you don’t have to be alone in the editing process either. You can make use of your network of colleagues, friends, supervisors, mentors, etc to help with this process.

Editing really is the key remedy to almost all issues of writing. It seems so simple, but Becker has found:

“What the students accept less easily is that, however long it takes, such detailed editing is worth doing.”

It really is. If you take away anything from reading this it’s this: EDIT YOUR WRITING !!!

Give away the ending

Student essays (and many academic papers) often start with vague introductions which don’t really say anything, and certainly do not contribute to the reader’s understanding of their argument. In Elements of Story Flaherty calls such an introduction the “um lead”:

“They [writers] often spend the initial paragraphs clearing their throats (…) This Um lead is not useless. The very act of writing helps a person sharpen her thoughts. But when she does arrive at the actual heart of the story, she must be sure to scroll up to the top and lop off those two and a half paragraphs of ‘Um’.”

So while all this writing fluff helps organise your thoughts, it should be cut out in the editing phase.

This is echoed in Writing for Social Scientists:

“Many social scientists (…) think they are actually doing a good thing by beginning evasively. They reveal items of evdidence one at a time, like clues in a detective story, expecting readers to keep everything straight until they trimphantly produce the dramatic concluding paragraph …I often suggest to these would-be Conan Goyles that they simply put their last triumphant paragraph first, telling readers where the argument is going…

And to those who are reluctant to give away the ending, for fear of the reader not making it to the end, Becker reassures us that “scientific papers seldom deal with material suspenseful enough to warrant this format”.

Get to the point

Related to the idea of ’throat clearing’ is the use of abstract, meaningless words, sentences, and even paragraphs which do not contribute to the reader’s understanding, and may even work actively against this. To use definite, specific, and concrete language is the a key principle of composition in Elements of Style:

“If those who have studied the art of writing are in accord on any one point, it is this: the surest way to arouse and hold the reader’s attention is by being specific, definite, and concrete.”

My students frequently complain about not having enough words to express their thoughts within the essay’s word count constraints. However these same students use up hundreds of words on indirect and vague sentences which contribute nothing to the paper’s argument. Once you delete these words, phrases, sentences, and even paragraphs, there will be plenty of words to spend on making clear arguments.

So why do we use these unnecessary words? Becker offers:

“We scholars use unnecessary words because we think, like the student in my seminar, that if we say it plainly it will sound like something anybody could say, rather than the profound statement only a social scientist could make.”

But it is better to be clear than to be fancy. Helen Kara says in Writing for Research:

“In academic research you will have a word count, but it’s a maxiumum rather than a target. You won’t lose any marks for saying everything you need to say in fewer words, and you will always gain marks for clarity.”

There are many reasons why we might have a build up of useless words. Becker raises two common examples:

1: Sometimes authors recognise that readers may disagree with them, and their insecurity adds unnecessary justifications. For example, he offers the sentence: “It is important to make the theory’s steps explicit.” as something redundant; it is obvious this is important, because only important things should be in your paper. Such sentences can be removed.

2: Social science writing loves sentences with three predicate clauses. For example: “This book excites our curiosity, gives us some answers, and convinces us that the author is right.” Like Becker, I am also guilty of using this form whether I have three things to say or not. This forced third unnecessary word does no work. “It doesn’t further an argument, state an important qualification or add a compelling detail. (See?)”. So don’t force that third unnecessary word, when two (or even better: one) is enough.

So how to address this? Be ruthless in your editing. Strunk and White say it best in Elements of Style :

“Omit needless words. Vigorous writing is concuse. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unneccessary sentences …”

Becker is not stressed, he says:

“No harm. It comes out in the editing.”

Avoid the “classy locutions”

Related to the use of too many words, but something which deserves its own theme is to avoid what Becker calls (I think ironically?) “classy locutions”. He describes having edited the work of a graduate student, going through and simplifying phrases. For example, he replaced “could afford not to have to be concerned with” with “needn’t worry”, and “unified stance” with “agreement”, and so on. Upon seeing this, the graduate student agreed this was shorter, and clearer, but insisted that “the other way was classier”. She said:

“Somewhere along the line, probably in college, I picked up on the fact that articulate people used big words, which impressed me…”

And this is something I see throughout academic work. So it is really, really, REALLY important for me, that I can say this (quoting Becker):

“None of these classy locutions mean anything different from the simpler ones they replace. They work cereonially, not semantically.”

The point is also picked up in two principles of Elements of Style:

1: “Do not overwrite”:

“Rich, ornate prose is hard to digest, generally unwholesome, and sometimes nauseating.”

and 2: “Avoid fancy words”:

“Avoid the elaborate, the pretentious, the coy, and the cute. Do not be tempted by a twenty-dollar word when there is a ten-center handy, ready and able.”

The point is echoed by Flaherty in Elements of Story:

“Banish long, obscure or Latinate words, too. “Housing complex” and “residential development” are each two words, but the first is better. The number of syllables matters as much as the number of words.”

We get attached to locutions and formats, but it is important to reflect on what do they really add to your paper, and if nothing, then the remedy takes us back to the point about editing. Remember: delete the excess.

Besides classy locution, I wanted to add a point here about writing with numbers that is mentioned in Elements of Story: avoid needless complexity. Consider this example of miniature Eiffel Tower figurines:

“The nation may have imported 340,684 miniature Eiffel Towers in the last year, but the reader will more easily absorb a round number “about 340,000.”

When we talk about communicating statistics, we often present estimates surrounded by uncertainty, but print these estimates to 3 decimal places. This sends a message of certainty where there is none. Not to mention, sometimes decimals detract from what the numbers actually mean. The average number of burglaries per neighbourhood might be 3.752 burglaries per 100 households, but there is no such thing as three quarters of a burglary, so we might as well round up to a whole number, which better corresponds to what we are quantifying in the first place.

Another way to reduce complexity is by interpreting numbers for your reader. When giving this feedback to students I borrow a phrase from Blastand and Dilnot’s book The Tiger That Isn’t, which simply asks:

“Is that a big number?”

When presenting numbers, I expect to have some context as a reader to help me interpret the numbers presented. Flaherty in Elements of Story suggests a way to do this by finding smart ways to compare magnitudes:

“’[A] million is to a billion as 11 days to 31 years’, and use familiar referents, like ‘A rhino weighs as much as 20 Michael Phelpses’.”

Whether presenting numbers or writing about concepts and theory, keep things simple, define and interpret things in their context, and impress the reader with clarity, rather than fancy language.

Show rather than tell

“Show rather than tell” is possibly my most commonly given feedback on student essays. When I read a sentence like “There is strong support for this argument”, I immediately think these words could have been used to present evidence of this support, rather then tell me to trust their word for it. In Elements of Story, Flaherty suggests that:

“‘Show, don’t tell’ works because showing is a telling, just a more vivid one.”

In academic writing, you should be showing with evidence that the argument is supported more often than telling the reader to take your word for it. Becker raises this point in Writing for Social Scientists with the example sentence: “There is a complex relationship between A and B”. This sentence says nothing - it is a place holder, which means nothing in itself, and needs to be illustrated. Instead, we can better present our arguments by describing what we have studied in specific detail.

Once this evidence is presented, there is no longer a need for a sentence like “There is strong support for this argument”, because this has been illustrated. This removes the need to explain too much. In Elements of Style Strunk and White advise:

“It is seldom advisable to tell all.”

Once you’ve presented the evidence, and put your numbers and arguments into context (abstaining from ‘fancy locutions’) the reader will arrive to your conclusions on their own.

Tell a story

Another issue I see in essays is the loss of the main argument in a sea of other writing. Often students are great at listing what they have read, and their data sources, and their analysis, and even their conclusions, but then miss the opportunity to tie everything together, and present it as a cohesive whole. One way to think about this is to think about telling stories.

Becker observes in Writing for Social Scientists:

“Perhaps as a result of my experiences in teaching, I have become more and more convinced of the importance of stories - good examples - in the presentation of ideas.”

Stories in the form of “good examples” could be told by including actors Elements of Story:

“Whatever your subject, give it a human face if you can.”

This probably more relevant to journalists, but may apply to some academic papers, or conference presentations as well. Flaherty suggests to put actors, not just talkers in your story. For example: “The tight housing market is also the old lady evicted with her four cats”. But, while such a “face” might not always be possible, the importance of having a focused story is relevant to any academic paper. Flaherty suggests that all stories are divided into two parts, the action and the commentary. It is important to balance these, giving enough detail (context) but maintaining profluence - the sense that things are moving, getting somewhere, flowing forward:

“Keep the boat moving and, at the same time, describe and explain the scenery to its pasenger.”

To keep your story focused, you might think about it in terms of the trunk and the branches. If your paper is a tree, the main argument is the trunk, and any details are the branches. To make writing clear, don’t leave your reader wondering: “What’s the trunk and what’s the branch?”.

This is especially common to see in literature review sections. The source of the problem is highlighted by Becker in Writing for Social Scientists: “Scholars must say something new while connecting what they say to whats already been said, and this must be done in such a way that people will understand the point”. So while we must engage with what had been done and recognise that "[o]ther people have worked on your problem, or problems related to it … you just have to fit them in where they belong”, we must take care, as .”..paying too much attention to [the literature] can deform the argument you want to make. It might bend your argument out of shape". The literature review must engage with existing scholarship in the area, but this should be all done with the aim to motivate the main argument of the paper. To achieve this, Becker suggests:

“The logic of your argument should guide your paper.”

How to do this? Flaherty in Elements of Story suggests that the struggle over trunk and branch is often one of relative length.

“Branches are slender, trunks are thick.”

If a main idea is set out in three paragraphs, the qualifications should get about one paragraph. If the main idea is one paragraph the qualifications only one sentence. The further the topic is from the heart of the story (your main argument), the fewer words it merits.

Keeping branches slender is achieved most effectively through exclusion.

“To write is to choose, which is to exclude. (…) Choose your main theme and position it, uncrowded, at centre stage.”

You choose a theme, an argument, a focus which will guide the writing. This doesn’t mean to ignore all the unchosen themes, you can nod to these. But devote most of your space to the big focus.

Use active voice over passive

I have heard this writing advice repeatedly. Do not use the passive voice. Always use active voice. It makes for stronger writing. But it wasn’t until I read the arguments made in Writing for Social Scientists that it really clicked for me why this is important.

“Active verbs almost always force you to name the person who did whatever was done (…). We seldom think that things just happen all by themselves, as passive verbs suggest (…) Sentences that name active agendas make our representations of social life more understandable and believable. “the criminal was sentenced” hides the judge, who we know, did the sentencing and not, incidentally make the criminals fate seem the operatoin of impersonal forces.

Specifically for social science writing this is interesting. At a conference once, Marcus Felson suggested that many sociologists think as if people didn’t have bodies, in which they do the living, perceiving, acting, etc. Relatedly, describing social concepts in passive tense removes agency. Becker explains:

“One problem has to do with agency: who did the things that your sentence alleges were done? Sociologists often prefer locutions that leave the answer to that question unclear, largely because many of their theories don’t tell them who is doing what.

If you say for example: “deviants were labelled” , you don’t have to say who labelled them. And this issue is substantial:

“That is a theoretical error, not just bad writing. (…) If you leave out the actors, you missstate the theory.”

This revelation really drives home the point to prefer active over passive voice in academic writing.

Final thoughts

It was good to read a little about writing, and learn some techniques to implement going forward. I’m sure there are many other books I could have learned from, and I look forward to finding more resources and eventually building up even more confidence in this area in the future, but for now, taking these points on board will definitely improve my writing. Not just the quality of the writing, but my experience of the process, and hopefully my productivity as well. And I hope that it is useful for others who want to improve their writing. Now let’s start this editing process rather than ramble on trying to reach some conclusion. As Strunk and White say:

“Omit needless words!”